Astronomers Detect Rare Collision of Mismatched Black Holes

For the first time, astronomers have detected two black holes with vastly different masses colliding into each other. The collision event, called GW 190412, was discovered back in April of 2019 by astronomers scanning the cosmos for signs of gravitational wave distortions. After analyzing the data provided by the collaborative efforts of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and the Virgo interferometer, astronomers found a rather large mass discrepancy between the two black holes. All of the black holes we've detected ramming into each other share a relatively equal mass, but, in this case, one of the black holes was nearly three-four times larger than the other.

LIGO-Virgo and Gravitational Waves

Since the beginning of the LIGO-Virgo collaboration, the results have proven incredibly fruitful—the very first observation run yielded the first concrete detection of gravitational waves (which won Rainer Weiss, Kip Thorne, and Barry Barish the Nobel Prize in physics). By the end of their second observations session with LIGO-Virgo, the team of astronomers realized that, though the discovery of gravitational waves from colliding black holes was groundbreaking, that particular type of black hole collision was quite common. They found so many that they named them ‘vanilla black holes.’ Each of these collision events follows a similar pattern, as both black holes are roughly the same size. A member of the collaboration team, Christopher Berry, writes in his blog “By the end of our second observing run, we had discovered that GW150914 (the name of their previous discovery) was not rare! Many of the detections consisted of two roughly equal mass black holes around 20 to 40 times the mass of the Sun.”

GW 190412’s Mass Discrepancy

During the third observation run for LIGO-Virgo, the team discovered GW 190412—a binary black hole collision event occurring nearly 2.4 billion light-years from Earth. The first black hole was about 30 times the mass of the Sun, while the other was just over 8 times the mass of the Sun. Berry states that “Neither of these masses is too surprising on their own. We know black holes come in these sizes. What is new is the ratio of the masses. This (ratio number) is roughly equal to the ratio of filling in a regular Oreo to in a Mega Stuf Oreo.”

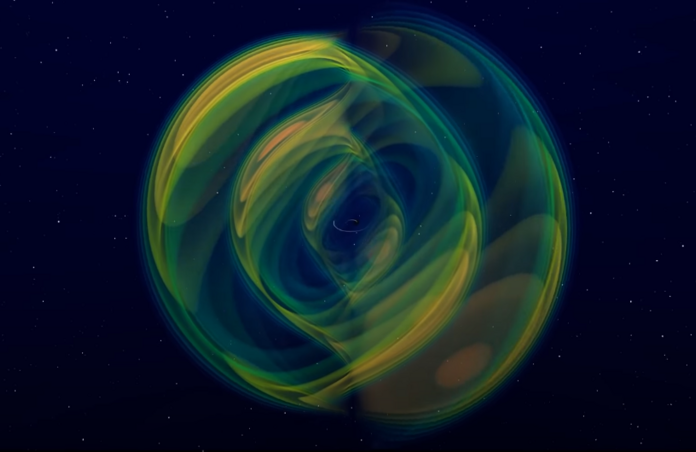

They discovered GW 190412 by analyzing gravitational wave frequencies. Gravitational waves emitted from black holes of equal mass stay the same frequency, but since one of the black holes was smaller, the wave frequencies were distinctly different. The distinct frequency allowed the team to make measurements of some other things as well, such as the spin of the more massive black hole—which is notoriously difficult to determine.

Black Hole Population

The discovery raises a lot of questions about the types of binary black holes LIGO-Virgo is studying. The team used ten previously detected binary black holes to set a baseline of what to expect, but the mass discrepancy of GW 190412 throws off the calculations a bit. Its existence also raises questions about how such a system came to be in that state of imbalance. Did it come from an isolated evolution with only two stars? Or did it form in a violent and dense cluster, where the black holes are constantly eating each other? Based on the exceptional results coming from the LIGO-Virgo collaboration, when these questions will be answered may simply be a matter of time.