Astronomers Find New Evidence of ‘Missing Link’ Black Hole

A team of astronomers has finally discovered definitive evidence of a mid-size black hole—the rarest and most elusive type of black hole. Compared to stellar (small) or supermassive ones, mid-size black holes, known as intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs), are incredibly challenging to locate. Formation models suggest they reside primarily in the outskirts of massive star cluster galaxies, instead of somewhere in the middle like most black holes. Researchers have detected only a handful of possible IMBH candidates, and, until now, none of them have been conclusively proven to exist.

Despite their light-devouring nature, astronomers are getting better at locating both stellar and supermassive black holes. They’re found by a locating a point in space emitting a massive gravitational influence on the objects around it—or when they’re shredding a nearby star or gobbling up some matter. Even the smallest of black holes, known as stellar black holes, have a mass greater than 100 times that of the Sun. However, though we've found evidence of plenty of both stellar and supermassive black holes, IMBH's remain ever elusive. They're less active and have a far weaker gravitational pull than their supermassive counterparts. IMBH's have long been considered the ‘missing link’ in the study of black hole evolution.

Finding the Missing Link

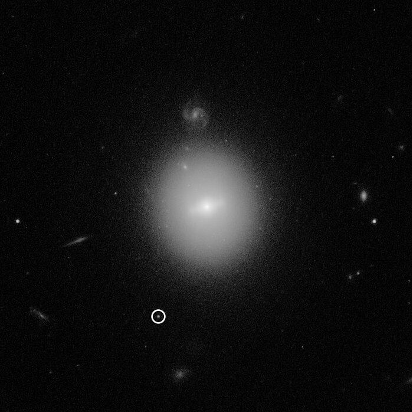

A team of astronomers, led by Dacheng Lin of the University of New Hampshire, have provided evidence for the existence of an IMBH by studying old X-ray data collected from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the ESA’s X-ray Multi-Mirror Mission (XMM-Newton). Back in 2006, both Chandra and XMM-Newton detected powerful X-ray flares emanating from an unknown source. Using the Hubble Telescope, the team followed up on these observations and traced their origins. After ruling out a nearby neutron star, which also gives off X-ray emissions, they found that the X-rays had emanated from a black hole named 3XMM J215022.4-055108.

They discovered the IMBH on the outskirts of a star cluster in a dwarf galaxy beyond the Milky Way. The team caught the mid-size black hole in the act of destroying a nearby star, which is what gave off the intense X-ray flares. Once they nailed down its precise location, the X-ray flares allowed them to calculate the mass of the IMBH—at over 50,000 times the mass of the Sun.

Finding More Mid-Size Black Holes

The finding and confirmation of an IMBH is an integral step in our understanding of black holes. Their study, which was published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, may even provide answers to questions surrounding the mysterious evolution patterns of supermassive black holes. Natalie Webb, a fellow contributor to the study, said, "Studying the origin and evolution of the intermediate-mass black holes will finally give an answer as to how the supermassive black holes that we find in the centres of massive galaxies came to exist.”