A cosmic game of fetch

Images of dog-bone shaped asteroid Kleopatra and its two twin moons set the standard for ESO’s upcoming generation of adaptive optics technologies.

Kleopatra is quite an unusual asteroid – not only does it have a bone shape, it’s also surrounded by at least two moons. While Kleopatra itself was detected as early as in the 19th century, it was only in 2008 that its moons (AlexHelios and CleoSelene, after the real Cleopatra’s twins), were found, less than a decade after the first asteroid’s moon. This recent field of enquiry now benefits from high-performance equipment that leads to unprecedently detailed observations. The cover image shows a take with the Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch (SPHERE) instrument at the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope’s (VLT) in Chile. Note that SPHERE has only been used since 2015, so it was truly difficult to analyse previous, low-resolution images of AlexHelios and CleoSelene.

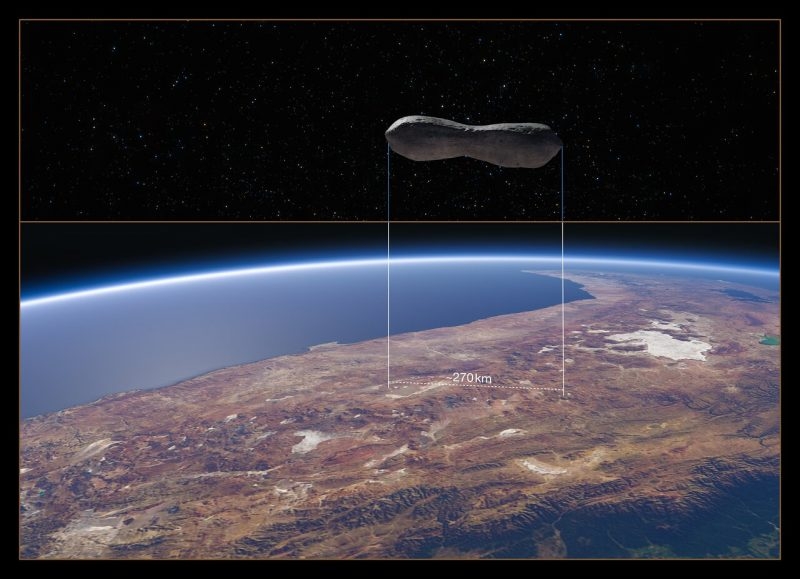

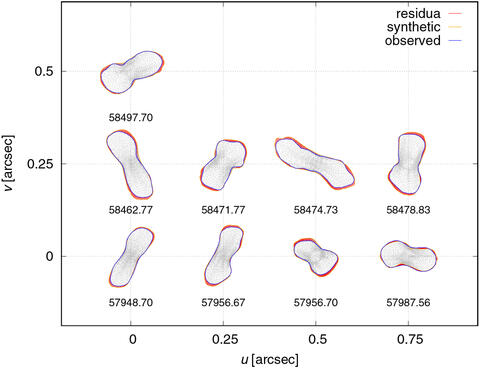

Back to the shape of the asteroid, it was known from radar observations at the now fallen Arecibo Observatory that Kleopatra appeared to exhibit two lobes and a thick “neck”. SPHERE took its series of images of Kleopatra between 2017 and 2019. As the rock tumbles through space in its orbit around the Sun in the Main Belt, a terrestrial observer faces it from different angles. This is how the researchers were able to calculate its length, 270 km (168 miles), as well as modelling the asteroid’s shape in more details. It notably appears as one of the lobes is larger than the other.

Kleopatra viewed by SPHERE at different angles as it rotates

Modelling the Kleopatra asteroid

Furthermore, the data from that 3D computer model could then be used to reformulate the motion of Kleopatra’s two moons based on the complex gravitational interactions provoked by the bone-shape. This in turn led the team to recalculate Kleopatra’s mass, finding it to be about 35% lower than past estimates, a good indicator that it’s not mainly composed of metals like previously thought, but rather that it has a porous structure. The researcher’s conclusion is that Kleopatra must have formed as a reaccumulating of material following a giant impact elsewhere in the Solar System, and that the moons formed from pebbles that got lifted off the asteroid’s surface following smaller impacts.

A key step to achieve more precise observations over the past two decades has been the use of adaptive optics. These correct for the effects of turbulences in the atmosphere (which cause “twinkling”), for a relatively small and faint object like Kleopatra, which essentially appears the same size as a golf ball about 40 kilometres away, these can be really significant. Thankfully, ESO is a leader in this field; recently their experimental CaNaPy Laser Guide Star Adaptive Optics system, designed for ESA’s Optical Ground Station in Tenerife, was found to be three times more powerful than any previous adaptive optics laser. This opens up further prospects, too, including communication with satellites via ultra-fast bandwidth optical signals.

Another technology that ESO is working on is the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), whose first light is being planned for 2027 and which will also eventually be pointed at Kleopatra. Astronomers hope to find even more moons, or evidence for other unforeseen phenomena occurring on or near asteroids.

Cover Image: Kleopatra and moons, ESO / Vernazza, Marchis et al. / MISTRAL algorithm (ONERA/CNRS)

Image Credits:

1 - Size comparison over Chile, ESO

2 - Images of Kleopatra with SPHERE, ESO / Vernazza, Marchis et al. / MISTRAL algorithm (ONERA/CNRS)

3 - Fig. 8 from "An advanced multipole model for (216) Kleopatra triple system", Broz et al., 2021

4 - CaNaPy laser undergoing commissioning, ESO