IXPE gets ready to scrutinize exotic objects

Although everyone has their eyes set on the upcoming launch of the James Webb Space Telescope, NASA has placed another satellite into orbit this week: IXPE.

The Falcon 9 launch

IXPE spacecraft separates from the rocket

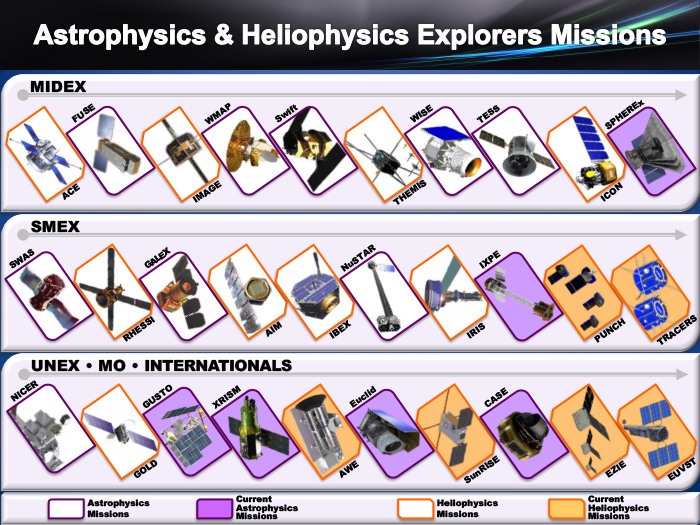

The Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE) mission is a collaboration between NASA and the Italian Space Agency that will notably build on discoveries made by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. Unlike its more famous counterpart though, IXPE is in low-Earth orbit (some 600 km above ground): this is because it’s a much smaller spacecraft, weighing “only” 325 kg, i.e., three times less than Chandra, which makes it a Small Explorers Mission (SEM).

SEMs were started by NASA in 1989 to “provide frequent flight opportunities for scientific investigations from space” – the programme has funded over 70 such small missions targeting very specific holes in our understanding of the Universe, on topics ranging from solar physics to galaxy evolution. Costing $160 million, IXPE fits perfectly within that framework and, as the name suggests, will be the first tool to be fully dedicated to studies of X-ray polarisation.

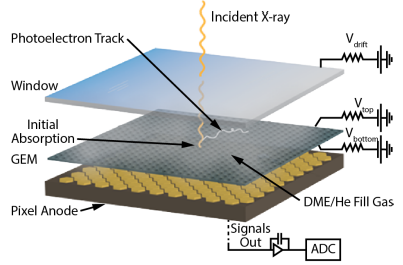

To achieve its purpose, IXPE is equipped with 3 telescopes – this creates a practical way of folding it into a small space for launch – and a state-of-the-art detector provided by the Italian part of the team: the Gas Pixel Detector (GPD). As an X-ray enters the GPD, it starts ionizing the gas in it; this means that electrons are emitted.

The key thing is that they are not emitted in random directions, but according to the direction of the electric field of the X-ray photon, that is, the direction of its polarisation. On top of the easily measured energy, position, and timing of the photon, astronomers can now access another quantity, the degree of polarisation: if all or a certain percentage of the rays from a given source point in a non-random direction, it has implications for the environment in which the X-ray was produced.

What about these environments ? Well, IXPE is going to look at some of the most intense and violent objects of our Universe, including supernovae, black holes, neutron stars, pulsars and magnetars, and quasars. Pulsars are a type of neutron stars that rapidly rotate around their own axis, thus emitting a periodic “pulse” of high-energy rays, while magnetars are the type that have unusually powerful magnetic fields. Quasars on the other hand are super-luminous active galactic nuclei. All of these have something in common: they are very, very energetic, which means that they are all sources of X-rays. However, the production mechanism in each case is quite a complex process that astronomers don’t fully understand, so IXPE is particularly timely.

While the launch of the triple-telescoped mission was successful, observations (and therefore potential answers about the physics behind extreme objects) can only start coming in after the “coilable boom” is deployed next week. Fortunately, a Tip/Tilt/Rotate mechanism is in place in case a few adjustments are needed to align IXPE.

IXPE is a somewhat underrated mission that will pierce the mysteries of the Universe’s most exotic objects.

Cover Image: Artist illustration, NASA

Image Credits:

1 - Falcon 9, NASA/J. Kowsky

2 - IXPE separates, NASA

3 - Explorers Missions, NASA

4 - GPD, NASA Marshall Space Flight Centre

5 - Centaurus A, NASA/CXC/U.Birmingham/M.Burke et al.

6 - IXPE Deployment, NASA/Anonymous Gifmaker