Popular Astrophotography targets (supernova remnants) reveal some of their secrets

Wonderful Chandra observations show that the “Hand of God” supernova remnant MSH 15-52 is slowing down, while studies of SN 2018zd confirm predictions about the existence a third type of supernova.

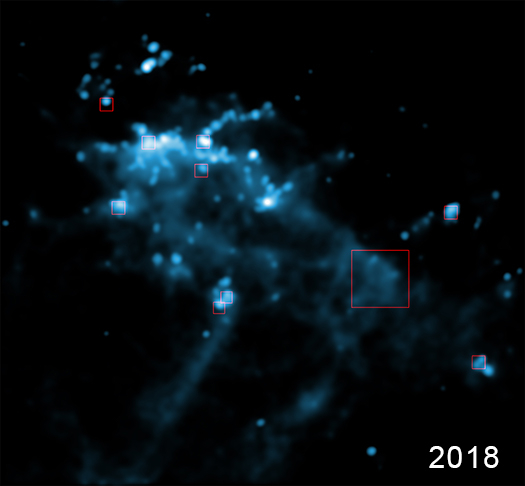

By comparing images from the Chandra X-ray observatory from the years 2004-2008 to some taken more recently in 2017-2018, a team at North Carolina State University was able to verify the speed at which gas from supernova remnant MSH 15-52 moves. The supernova explosion itself was detected about 1700 years ago, which makes it one of the youngest in our Milky Way galaxy. It left behind a pulsar, a neutron star with a magnetic field that influenced the shape of the ejected gas into “fingers”.

Calculating the speed at which the gas would have to travel, based on the age of the supernova remnant and the distance between the centre of the explosion and the gas' current location, one gets about 30 million miles/hour (48 million km/h). From the Chandra observations, this value is currently much lower, at about 9 to 11 million miles/hour (14 to 17 million km/h). This can be explained by the fact that MSH 15-52’s “fingertips” are colliding with a surrounding wall of gas, RCW 89. Initially, the ejected gas would have passed through a low-density cavity of gas around the star, which probably was formed thanks to stellar winds from the star during stages before the supernova. This is a well-known process that notably produced the popular target for astrophotography Cassiopeia A, an even younger supernova remnant. However, for MSH 15-52 the expansion into space is halted by the presence of RCW 89.

This observation coincides with the confirmation of the existence of a third type of supernovae: electron-capture supernovae, which are similar to type II, core-collapse supernovae, in that after the explosion what remains is a neutron star; note that for type II the remnant can also be a black hole. As a reminder, during a type II supernova, the pressure of free electrons inside the core becomes insufficient to support the star’s gravitational compression force, once fusion to elements of the iron group has been reached. It was hypothesized in the 80s that stars with masses between 8 and 10 solar masses (the lower limit for type II) could undergo a slightly different process - Magnesium and Neon nuclei in the core start capturing the free electrons, reducing the electron pressure and causing the explosion. SN 2018zd, first observed in 2018 as the name indicates, fits all the theorised characteristics of an electron-capture supernova. This confirmation was done thanks to observations of its host galaxy before and after the explosion, with the Spitzer and Hubble space telescopes.

SN2018zd (large white dot at right) within the galaxy NGC 2146

The Crab Nebula, possibly also a remnant from an electron-capture supernova

It is thought that another very popular target for astrophotography, the Crab Nebula, could be the result from an electron-capture supernova too; but since the explosion was first seen in 1054 A.D., the initial type of star and the way its luminosity behaved during the weeks after the explosion can’t be established with certainty. Still, being able to determine how filaments from the leftover shell of gas behave, as was done in the case of the “Hand of God”, is a key step in understanding how a supernova and its remnant evolve.

Cover Image: Supernova remnant around pulsar PSR B1509-58, NASA/CXC/SAO/P.Slane, et al.

Image Credits:

1, 2 & 3 - Evolution of MSH 15-52, NASA/SAO/NCSU/Borkowski et al.

4 - SN2018zd, NASA/STScI/J. DePasquale and Las Cumbres Observatory

5 - Crab Nebula, NASA, ESA, NRAO/AUI/NSF and G. Dubner (University of Buenos Aires)