Betelgeuse is Seen Recovering After Catastrophic Blowout Event

The red giant star Betelgeuse has recently been observed by astronomers slowly repairing the damage caused from the infamous ‘great dimming’ event in 2019.

Betelgeuse is a colossal star known as a supergiant, which are elderly stars that swell up after running out of ‘fuel’ for nuclear fusion. Regarded as one of the brightest stars in our sky, Betelgeuse has expanded to a great diameter of 1 billion miles – if the star was placed in the centre of the solar system, it would reach Jupiter’s orbit! Scientists have been recording detailed observations of Betelgeuse for 150 years, uncovering the pulsating cycle the star follows as it grows and shrinks in size and brightness over a period of 420 days.

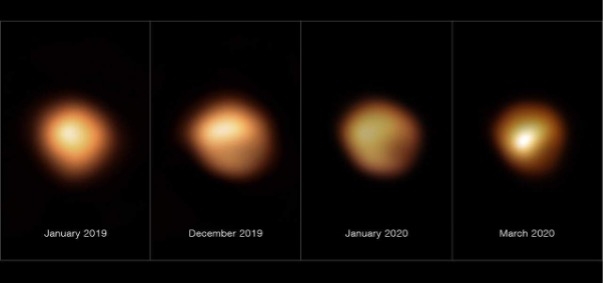

However, the star experienced an event known as the ‘great dimming’ in 2019 – the substantial star started to dim, reaching its faintest in early 2020. There was much speculation that this sudden decrease in brightness was a clue to its eventual death, and astronomers were expecting to see a rare but exciting sight: a supernova. Nevertheless, this turned out to not be the case but rather something more puzzling.

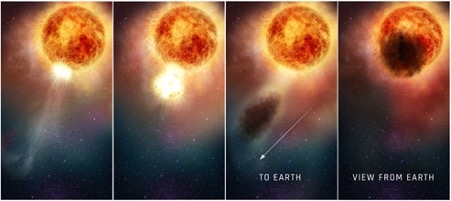

Graphic showing the expelled gas which subsequently formed a cloud of dust blocking the light to earth.

From recent observations and research, it was uncovered that Betelgeuse had likely undergone an enormous surface mass ejection (SME), which blasted off a sizeable chunk of its visible surface. In fact, the event was so massive that it blew off around 400 billion times the mass thrown out in a typical coronal mass ejection (CME) from the sun! Surface mass ejections happen when a star releases large amounts of magnetic flux and plasma into space. As the expelled mass moved away from the star, it cooled and produced a dust cloud which blocked the light, resulting in the dimming.

Nevertheless, it is not entirely clear what triggered the colossal SME, but a possibility is a convective plume spanning more than a million miles across which bubbled up from deep inside the star. The plume may have disrupted the convection cells that drove the periodic changes in brightness, producing shocks that blasted off a chunk of the photosphere.

In light of the catastrophic event, observations by Hubble have seen Betelgeuse recovering with its photosphere slowly rebuilding itself. However, although the outer layers may have returned to normal, the interior is bouncing around like jelly. Because of this, its regular 420- day cycle of dimming and brightening has disappeared, perhaps temporarily- only time will tell if its celestial heartbeat will restart.

The new observations of this unusual star are also providing insight into understanding how red stars lose mass as they age and subsequently halt nuclear fusion, and the consequences following these great eruptions. Due to the scale of the explosion being significantly larger than the plasma that is ejected from the suns corona, scientists think that SMEs are a different kind of event to CMEs.

Although Betelgeuse is one of the most attractive candidates for a star going supernova, unfortunately we will have to wait just a bit longer for that to happen, since there is no evidence which suggests that it’ll be meeting its fate anytime soon. Further monitoring of its brightness will be carried out and it is suspected that more dimming events will happen in 3 or 4 years. Additionally, NASAs James Webb Space Telescope can be used to detect infrared from the ejecta of these CMEs as it moves away from Betelgeuse.

--

Cover image: Getty images/NASA.

Image credit:

- ESO/M. Montarges et al.

- NASA, ESA, E. Wheatley (STScl)