First Direct Detection of CO2 in Exoplanetary Atmosphere

Exoplanetary research offers invaluable insights into the processes that shaped not only their own systems but also the history and formation of our own solar system. Ordinarily, such analysis requires an exoplanet to transit across its host star. As starlight passes through the planet's atmosphere, it is differentially absorbed by various molecules, creating absorption features that indicate the atmospheric composition. However, in theory, planets also emit their own continuous blackbody spectrum, albeit at much lower temperatures than stars. This emission is often faint and can be easily overwhelmed by the much brighter stellar spectrum, making it difficult to directly detect.

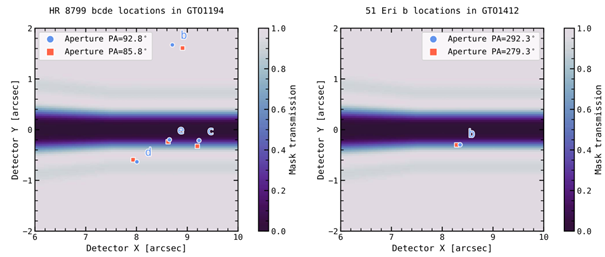

A new paper led by William Balmer presents efforts to directly image the planetary atmospheres in two exoplanetary systems. The study focuses on HR 8799 and 51 Eridani, both of which host recently formed planets. These younger planets are initially much hotter, and as they cool, emit a relatively observable spectrum, primarily within the mid infrared range. Their primary goal was to assess the formation mechanisms of giant planets by analysing their atmospheric compositions, particularly focusing on identifying CO₂ within these systems. The study also aimed to test the James Webb Space Telescope’s (JWST) ability to assess exoplanetary atmospheres directly, without needing to infer these based on starlight.

They leveraged the telescope’s NIRCam coronagraph for direct and spectroscopic imaging. This instrument is designed to suppress starlight and help isolate emissions from exoplanets or debris disks. To further remove the planetary light from the remaining atmospheric radiation, the team used similar reference stars to subtract the contribution of the star's light. The remaining features were then cross referenced with simulated models of the systems, to confirm whether these were actual detections or simply anomalies.

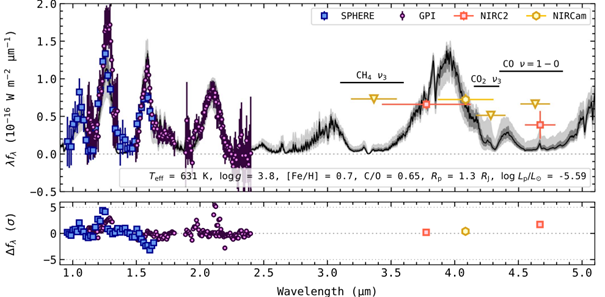

Indeed, the team successfully identified the CO₂ absorption features within these spectra. Surprisingly, however, these features appeared stronger than their initial models predicted, suggesting the metallicity of these planets had been enriched beyond standard solar abundances. They observed a radial trend in metallicity, as planets further from their host stars appeared less enriched.

These findings suggest that the planets in these systems formed via core accretion rather than gravitational collapse. In core accretion, a solid core gradually builds up from accumulating dust and ice, eventually becoming massive enough to capture an atmosphere primarily composed of hydrogen and helium. This process can take millions of years, allowing surrounding solid material to contaminate the atmosphere with heavier elements. Additionally, the inner regions of a protoplanetary disk are naturally richer in heavy elements than the outer regions, explaining the observed decline in metallicity with increasing distance from the star. In contrast, gravitational collapse occurs too rapidly for such compositional gradients to develop, as it forms planets directly from gas without significant metal enrichment.

The team also found that the orbit of 51 Eridani b is highly elliptical (e=0.57), which could be indicative of gravitational interactions with other yet unknown planets.

The results demonstrate the effectiveness of JWST’s NIRCam coronagraph in detecting, resolving and characterising close-by exoplanets. The team suggest future research should explore more exoplanetary systems with these methods and use higher-resolution spectroscopy to better probe atmospheric composition and formation histories.

--

Journal Source: W. Balmer et al, JWST-TST High Contrast: Living on the Wedge, or, NIRCam Bar Coronagraphy Reveals CO 2 in the HR 8799 and 51 Eri Exoplanets’ Atmospheres, The Astrophysical Journal Vol. 169, No. 4, (2025), DOI: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/adb1c6

Cover Image Credit: NASA