Astronomy News

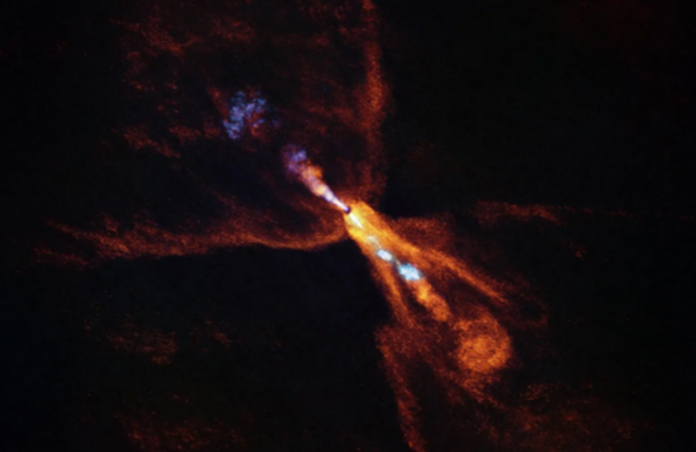

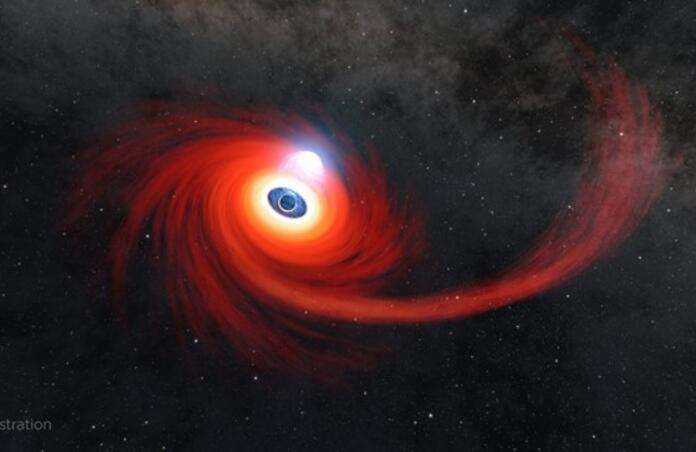

The Direct Measurement of A Black Hole Mass During the Era of Reionisation

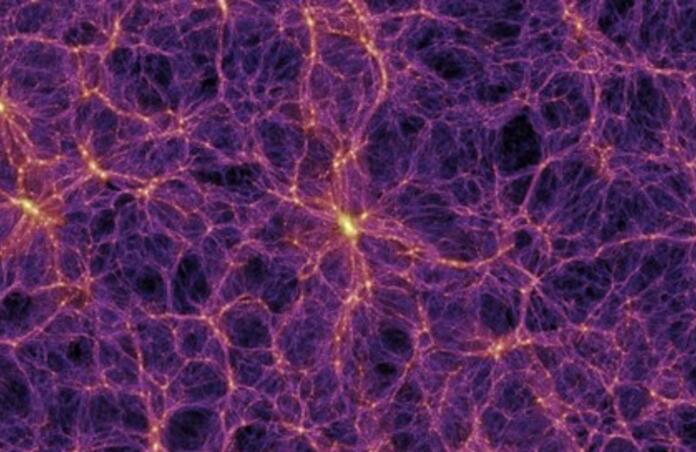

The Λ-Cold Dark Matter (ΛCDM) model successfully explains many large-scale cosmological phenomena, but the early presence of supermassive black holes (SMBHs) still poses a major challenge.

0

0