Seven-planet system uncovered by Kepler

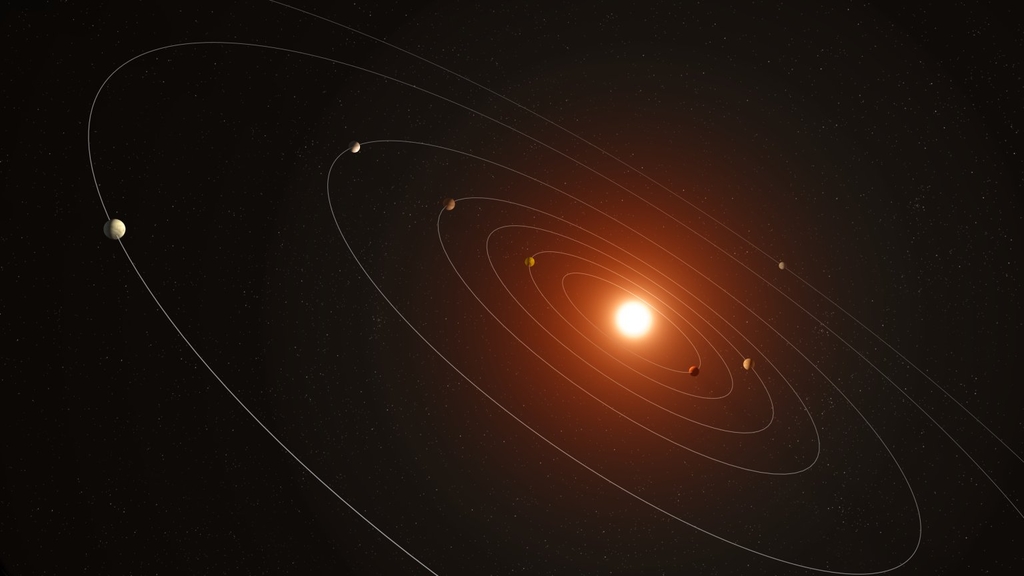

A team of researchers have revealed a seven-planet system, uncovered in the sea of kepler data despite the telescopes retirement in 2018. The star, denoted Kepler-385 is located around 4670 light years away and hosts seven planets with extremely close orbits.

The system isn’t exactly brand new, since some planets had already been confirmed in 2014. However, others remained as planetary candidates. Thanks to a new updated catalogue, the remaining candidates have been confirmed as planets, and new details on this intriguing system have been revealed. "We've assembled the most accurate list of Kepler planet candidates and their properties to date," said Jack Lissauer, lead author of the study. "NASA's Kepler mission has discovered the majority of known exoplanets, and this new catalogue will enable astronomers to learn more about their characteristics."

The new catalogue lists all known Kepler planet candidates that orbit and transit one star only. Concerning the Kepler-385 system, all seven planets are larger than Earth but smaller than Neptune. The star is similar to our sun, except it is around 10% larger and 5% hotter, being one of the few stars which host more than six planets or candidates. The innermost two planets are most likely rocky types with possible thin atmospheres, whereas the other 5 are twice the size of earth, likely bearing thick atmospheres. This system is just one among 4,400 planet candidates and 700 multi-planet systems within the catalogue.

"Our revision to the Kepler Exoplanet catalogue provides the first true uniform analysis of exoplanet properties," said co-author Jason Rowe, Canada Research Chair in Exoplanet Astrophysics and Professor at Bishop's University in Quebec, Canada. "Improvements to all planetary and stellar properties have allowed us to conduct an in-depth study of the fundamental properties of exoplanetary systems to better understand exoplanets and directly compare these distant worlds to our own solar system and to focus in on the details of individual systems such as Kepler-385."

With the help of Gaia, improved measurements of stellar properties have allowed researchers to analyse the distribution of transit durations. This is an extremely useful tool for probing exoplanet distributions. Although there isn’t enough data for most exoplanets to measure individual eccentricities, methods have been developed to characterise the distribution of such a measurement for a population of transiting exoplanets. This yields a crucial finding: a system with several planets has smaller, more circular orbital eccentricities.

"While previous studies had inferred that small planets and systems with more transiting planets tend to have smaller orbital eccentricities, those results relied on complex models," said co-author Eric Ford from the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics at Penn State University. "Our new result is a more direct and model-independent demonstration that systems with more transiting planets have more circular orbits."

Unfortunately, no life will be thriving on any of the Kepler-385 planets. All seven are constantly blasted with intense stellar radiation due to their close-in orbits. In fact, such planets receive more heat per area than any planet in our solar system.

Even after half a decade of the Kepler mission being shut down, the goldmine of data continues to reveal more about our galaxy and it’s inhabitants. What will be discovered next?

--

Cover image: NASA/Daniel Rutter

Journal source: Jack J. Lissauer et al, Updated Catalog of Kepler Planet Candidates: Focus on Accuracy and Orbital Periods, arXiv (2023). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2311.00238