Team measure dark matter halos around extinct quasars

After surveying hundreds of extinct quasars, a team led by Professor Nobunari Kashikawa from the Department of Astronomy has found the behaviour of these active objects to be consistent through time. This surprising finding may have implications for the evolution of the universe.

As stated by the current Lambda-CDM model, tiny fluctuations in dark matter density in the early universe grow and collapse into dark matter halos (DMHs). The subsequent continuous accretion and merging of these halos form high mass DMHs. It is believed that quasars, which are supermassive black holes (SMBH) that become active after reaching a certain size, are activated by massive DMHs that encompass the galaxy which the SMBH is located at the centre of. The halos direct matter towards the centre, therefore feeding the black hole.

However, considering the current uncertainty on the nature of dark matter, measuring the mass of such halos is fairly difficult. Dark matter can only be measured indirectly, through its gravitational effects on ordinary matter. This can either be how it pulls on other objects, or through the lensing of objects behind a suspected region of dark matter. In addition, the more distant the active object is, the fainter the light emitted is, since the light is absorbed by matter on its long journey as well as being stretched into infrared wavelengths due to the expansion of the universe.

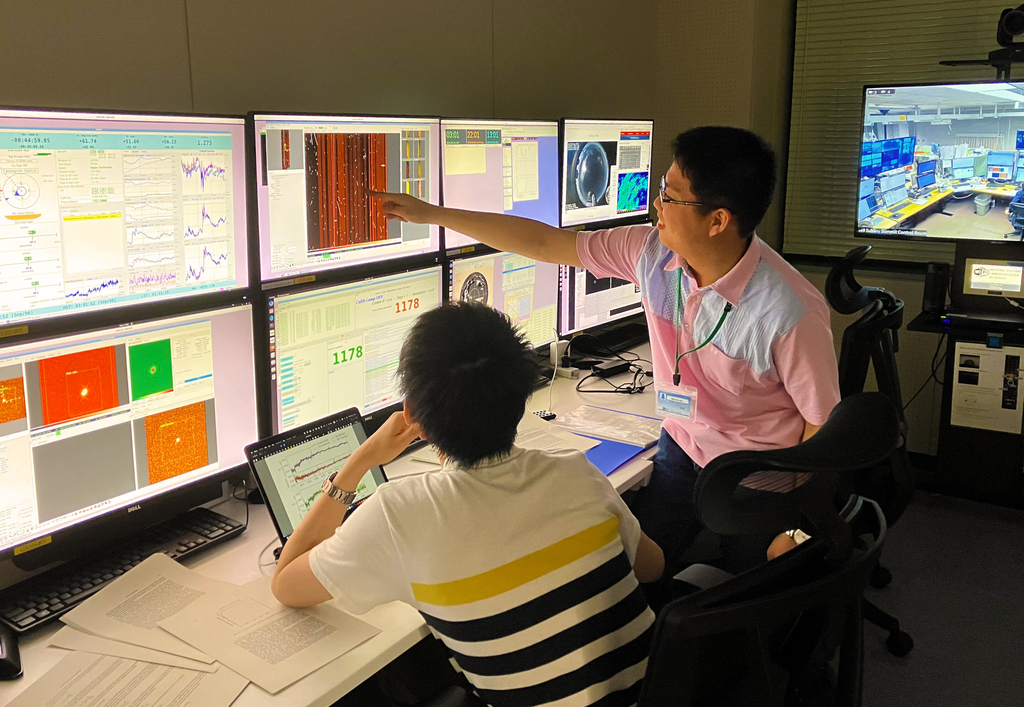

Despite the difficulties presented, the team began their project in 2016 in the search for the answers to many ongoing questions concerning dark matter: how are black holes born, and how do they grow? In particular, the team are interested in the SMBHs found at the centre of every galaxy. These gigantic phenomena can be studied due to the powerful jets of radiation they spew. The project involved using multiple surveys that involved a number of instruments, including Japan’s Subaru Telescope.

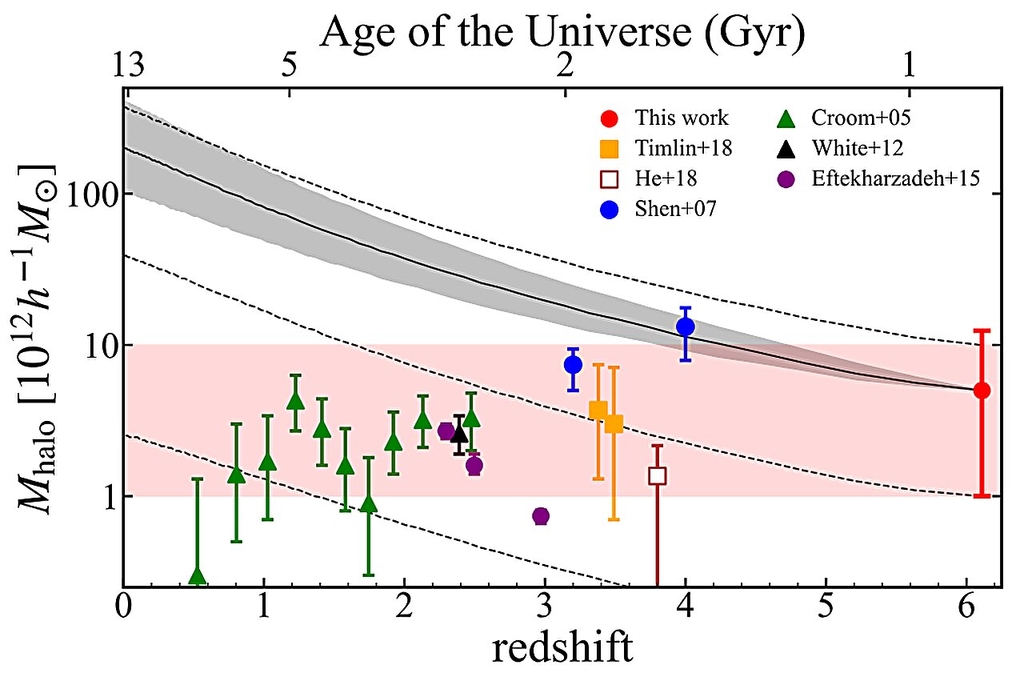

"We measured for the first time the typical mass for dark matter halos surrounding an active black hole in the universe about 13 billion years ago," said Kashikawa. "We find the DMH mass of quasars is pretty constant at about 10 trillion times the mass of our sun. Such measurements have been made for more recent DMH around quasars, and those measurements are strikingly similar to what we see for more ancient quasars. This is interesting because it suggests there is a characteristic DMH mass which seems to activate a quasar, regardless of whether it happened billions of years ago or right now."

"Upgrades allowed Subaru to see farther than ever, but we can learn more by expanding observation projects internationally," said Kashikawa. "The U.S.-based Vera C. Rubin Observatory and even the space-based Euclid satellite, launched by the EU this year, will scan a larger area of the sky and find more DMH around quasars. We can build a more complete picture of the relationship between galaxies and supermassive black holes. That might help inform our theories about how black holes form and grow."

—

Cover image: STScl

Journal source: Junya Arita, Nobunari Kashikawa, Yoshiki Matsuoka, Wanqiu He, Kei Ito, Yongming Liang, Rikako Ishimoto, Takehiro Yoshioka, Yoshihiro Takeda, Kazushi Iwasawa, Masafusa Onoue, Yoshiki Toba and Masatoshi Imanishi, “Subaru High-z Exploration of Low-Luminosity Quasars (SHELLQs). XVIII. The Dark Matter Halo Mass of Quasars at z ∼ 6,” The Astrophysical Journal: September 8, 2023, DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2307.02531.