Volcanic Activity Still Persists on Mars

It has been 4 years since NASA’s InSight mission deployed the SEIS seismometer on the surface of mars, with the aim to detect and characterise marsquakes. Since then, over 1300 quakes on the Martian planet have been detected, ranging in amplitude. New analysis carried out by a group of researchers at ETH Zurich on 20 of these rumbles has revealed that volcanic activity may still exist on mars and continues to shape the planet to this day.

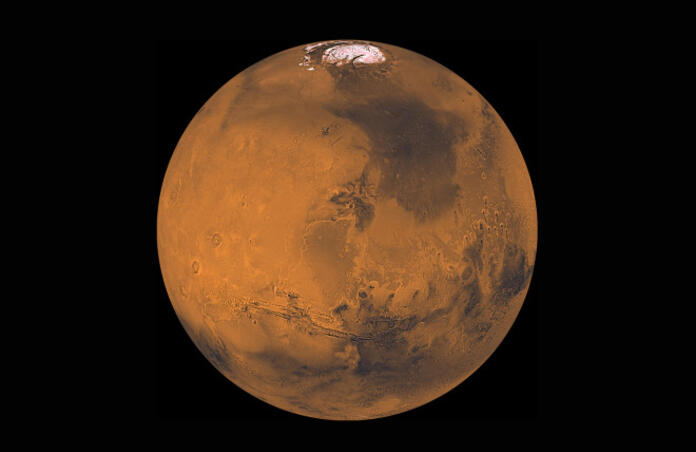

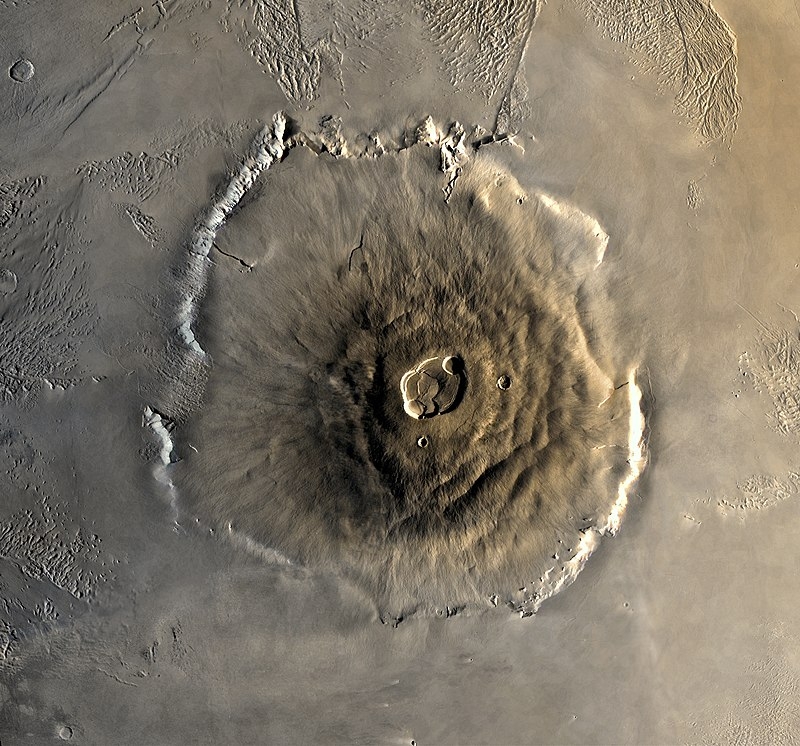

Although mars is thought of as an inactive planet due to its lack of magnetic field and tenuous atmosphere, in the distant past some 3.6 billion years ago the planet was much more ‘alive’. Mars was extremely volcanically active, releasing enough volcanic debris over a long period of time to produce the Tharsis Montes region – the largest volcanic system in our solar system. Additionally, the planet hosts Olympus mons, an exceptionally large volcano that stands 16 miles high, covering as much area as the state of Arizona. However, the red planet has drastically changed over its lifetime. Layers of sedimentary rock along with the presence of aqueous minerals suggest that mars once hosted bodies of liquid water, which is a very different story to the dusty desert we see now.

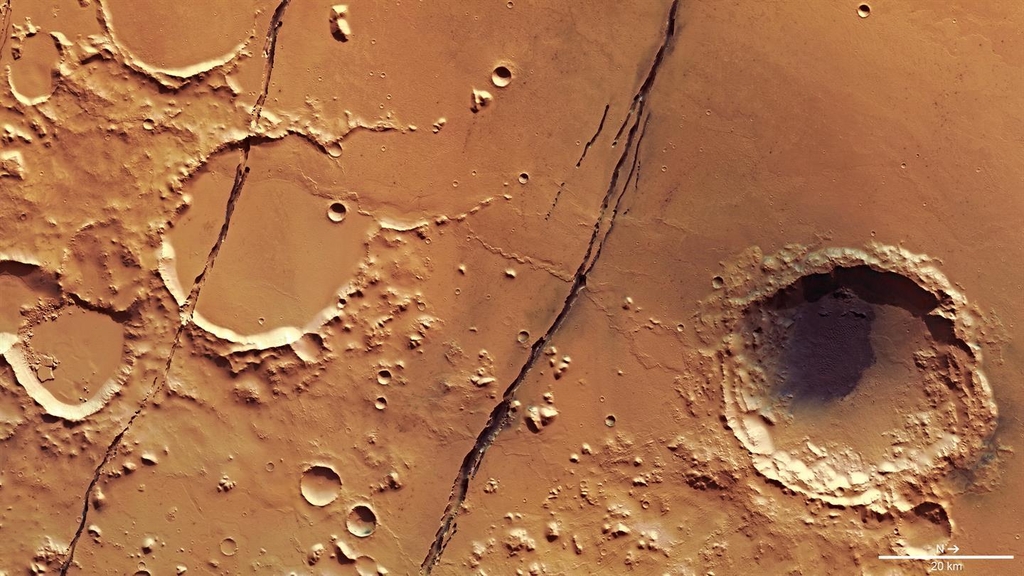

The team of researchers found that the epicentre of the marsquakes originated in the Cerberus Fossae vicinity, a region of parallel fissures that lie 11 degrees north of the equator. In fact, the Cerberus Fossae quakes were seen to represent at least half of the seismic activity present on Mars, making this an important region to further study. The data concludes that the low frequency of the quakes indicates a warm source located 30-50km below the Martian surface, which could be explained by present day underground magma and volcanic activity.

After comparing seismic data with observational images in the same area, the group also discovered darker deposits of dust in multiple directions surrounding Cerberus Fossae Mantling Unit. Their findings were published in the journal Nature, and lead author Simon Staehler states: “The darker shade of the dust signifies geological evidence of more recent volcanic activity—perhaps within the past 50,000 years—relatively young, in geological terms”.

It is believed that the weight at the epicentre region of the quakes is sinking and forming parallel graben that pull the planets crust apart. To quote Staehler, “it is possible that what we are seeing are the last remnants of this once active volcanic region or that the magma is right now moving eastward to the next location or eruption”.

By studying our neighbouring planet, we could better our understanding of similar geological processes on earth, a planet which is similar yet vastly different. For example, mars is the only known planet to have a core comprised of iron, nickel and sulfur that could have once hosted a magnetic field, and topographical evidence suggests that mars could’ve had a more substantial atmosphere.

If volcanic activity on the planet still persists to this day, this could have implications for the comprehension of the planet's geology, as well as the ongoing search for life that scientists believe could be found under the surface. Since liquid water lakes are thought to be present at subsurface levels, a heating source would be required to maintain a habitable temperature, therefore underground magma could be the answer scientists are looking for.

--

Cover image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/TAMU

Journal source: Simon Stähler, Tectonics of Cerberus Fossae unveiled by marsquakes, Nature Astronomy (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-022-01803-y. www.nature.com/articles/s41550-022-01803-y