Water vapour detected in planet-forming disk

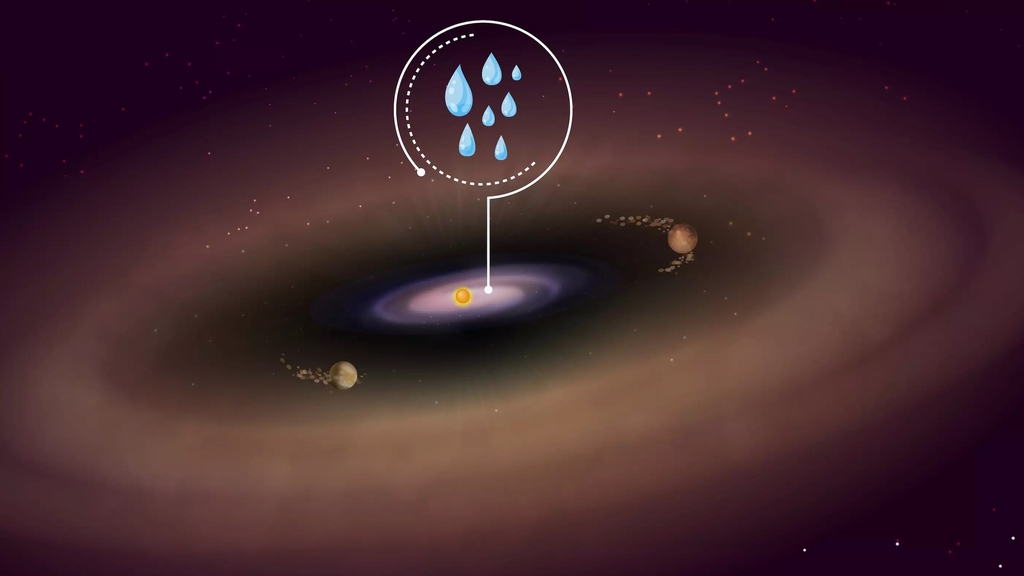

Water vapour has been detected in the inner disk of a planetary system, a region where rocky, terrestrial planets can form. This new finding may be evidence for water being available to such planets from the very beginning, contrary to previous study which implies that the early Earth received most of its water supply from the bombardment of water-bearing asteroids.

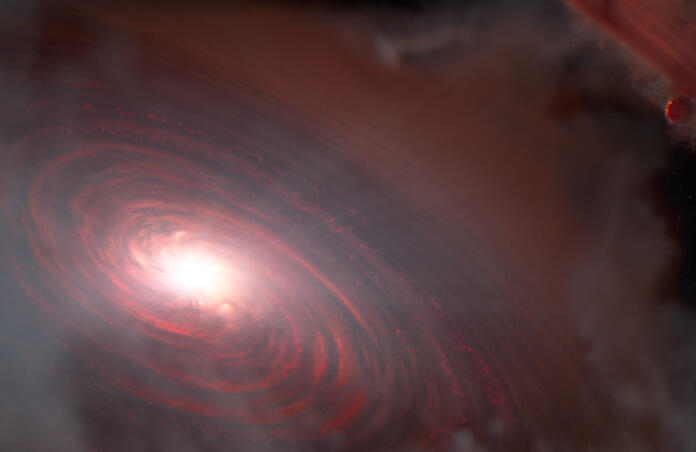

The planetary system of interest is PDS 70, located 370 light years away. The system consists of a 5.4-million-year-old K-type star which hosts an inner and outer disk of dust and gas. In between these two regions is an 8 billion km gap, within which two known gas giants orbit. "PDS 70 is a star similar to our sun, just younger and cooler," study lead author Giulia Perotti, an astrophysicist at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, told Space.com. "By observing it, we can trace back how the planets in our solar system formed and what their chemical composition was before they fully formed."

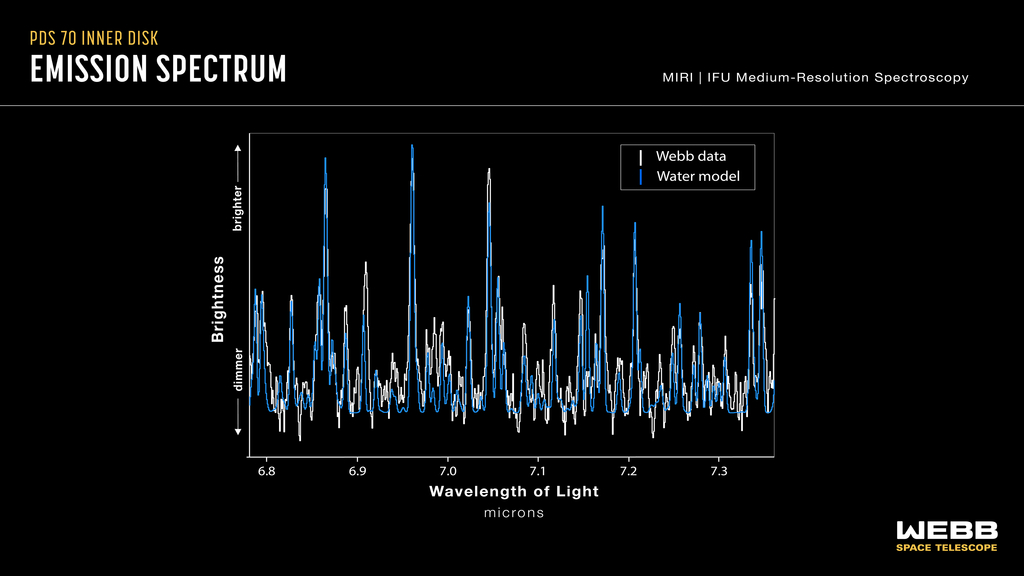

Water vapour was detected within the inner disk by JWST’s MIRI at distances less than 160 million km from the central star, reaching temperatures of 330°C. The unlikely detection is also the first of its kind, since water has never been seen in the terrestrial region of a disk known to host two or more protoplanets. "We've seen water in other disks, but not so close in and in a system where planets are currently assembling. We couldn't make this type of measurement before Webb," said Perotti.

Within our own solar system, the Earth and other rocky planets formed in the central zone. Applying this to the exoplanetary system found, any rocky planets within the same central zone of PDS 70 would already have a large reservoir of water, improving the chances of habitability. However, the existence of water vapour within this system was unexpected, since no detection of water in the central regions of disks with a similar age were reported. Because of this, it was presumed that water would not survive the harsh stellar radiation, resulting in a rather dry environment for any planets which form in this region. For now, no planets have been detected within the inner disk.

This leads scientists to the question: where did the water come from, and how did it survive? The team have considered two possible explanations for its origin. The first is that water molecules formed in space from the combination of hydrogen and oxygen atoms which enter the outer rims of the PDS 70 system. The second is the transportation of ice-coated dust particles from the cool outer disk to the hot inner disk, resulting in the sublimation of ice to vapour. However, the latter case would be surprising, since the dust would have to cross the large gap between the two disks. Regarding the survival of the water despite its close proximity to the star, it is most likely that dust and other water molecules act as a protective shield against the intense UV radiation.

To continue their research further, the team will use Webb's NIRCam and NIRSpec to study the system in more detail.

--

Cover image: NASA, ESA, CSA, J. Olmsted (STScI)

Journal source: G. Perotti et al. Water in the terrestrial planet-forming zone of the PDS 70 disk. Nature, published online July 24, 2023; doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06317-9